Clouds cover on average about two thirds of the globe and have a strong presence in Earth’s radiative energy budget. They cool the planet by reflecting about $50~\mathrm{W}~\mathrm{m}^{-2}$ of shortwave radiation back to space, or about 15% of incoming solar radiation. They also contribute to the greenhouse effect, by absorbing a sizable amount of infrared radiation emitted from Earth’s surface. Their net effect on the current climate is cooling, on the order of $20~\mathrm{W}~\mathrm{m}^{-2}$ (IPCC AR5, 2013).

Climate models aim to forecast changes in the Earth system due to, primarily, anthropogenic greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. These emissions result in an effective warming of $2.5-3.1~\mathrm{W}~\mathrm{m}^{-2}$ (Myhre et al. 2013). Given the large magnitude of cloud radiative effects, about 10 times stronger than the GHG forcing, biases in the representation of cloud-radiation interactions lead to large uncertainty in climate projections.

The main source of this uncertainty is the representation of clouds themselves. Clouds cannot be resolved in climate models due to resolution constraints. Instead, parameterizations of unresolved processes must be used to predict the presence of clouds within each climate model grid-box. Another source of uncertainty is the interaction of clouds with aerosols, which can foster cloud formation and change their reflective properties.

But subgrid-scale cloud processes and aerosol-cloud interactions are not the only sources of bias in cloud radiative effects. Climate models employ simplified radiative transfer solvers to compute the amount of radiation that clouds reflect back to space. An important simplification that radiative transfer solvers make is the computation of radiative fluxes exclusively in the vertical; a simplification known as the independent column approximation (ICA). Under the ICA, light scattered upwards can only be reflected back to Earth by clouds directly overhead. In reality, light scattered at an angle may encounter nearby clouds before it reaches the top of the atmosphere, returning back to the surface.

How important is this lateral scattering effect in practice? Although three-dimensional radiative transfer is intractable at a global scale, it is computationally feasible to try to answer this question using a smaller domain. An advantage of using limited-size domains is that we can also afford to resolve all dynamical cloud processes. By comparing three-dimensional radiative transfer calculations to those obtained using the ICA through the same cloud field, we can estimate the magnitude of the bias caused by the approximation.

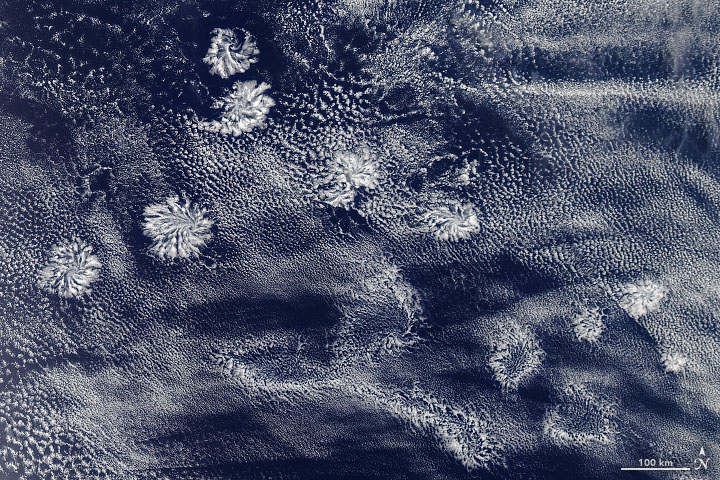

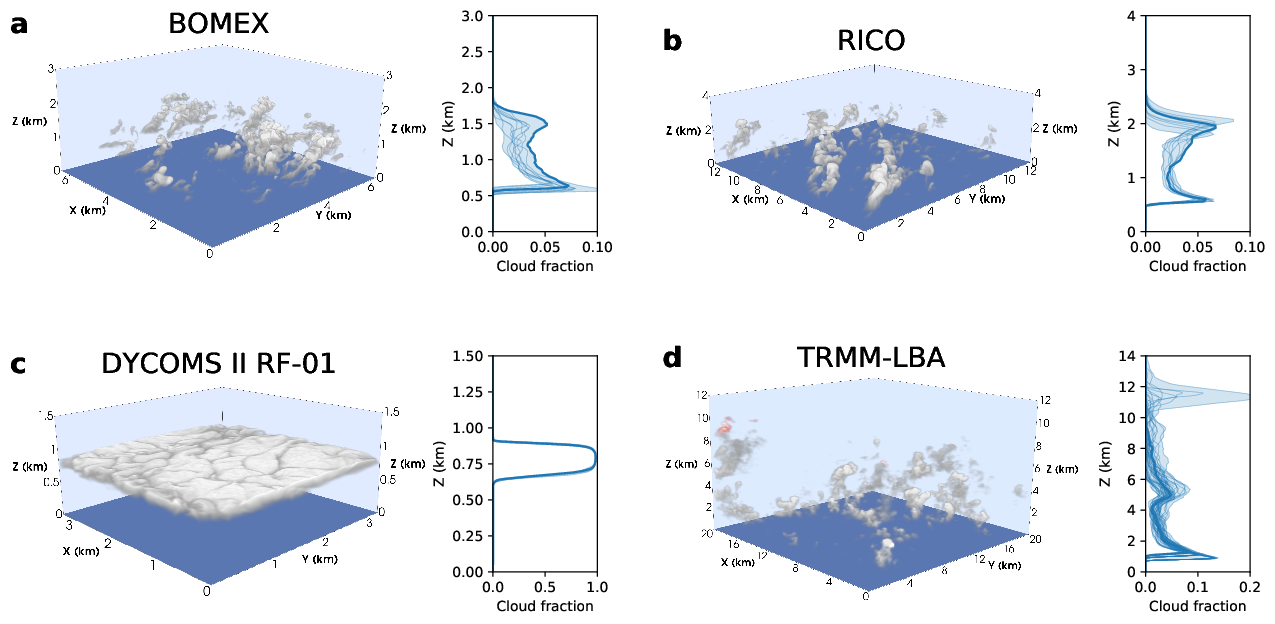

|

|---|

| High-resolution simulations of shallow cumulus (a,b), stratocumulus (c) and deep cumulonimbus clouds. These simulations can be used to estimate the effect of lateral light scattering on Earth’s albedo near the tropics (Singer et al. 2021) |

In an article published in the Journal of Atmospheric Sciences, we used an ensemble of cloud-resolving simulations to estimate the radiative effect of lateral light scattering (Singer et al. 2021). We found that, in the tropics, lateral light scattering reduces Earth’s albedo and results in a net warming effect of $3.1 \pm 1.6~\mathrm{W}~\mathrm{m}^{-2}$. Therefore, neglecting this effect in cloud-resolving models results in a cooling bias of the same magnitude.

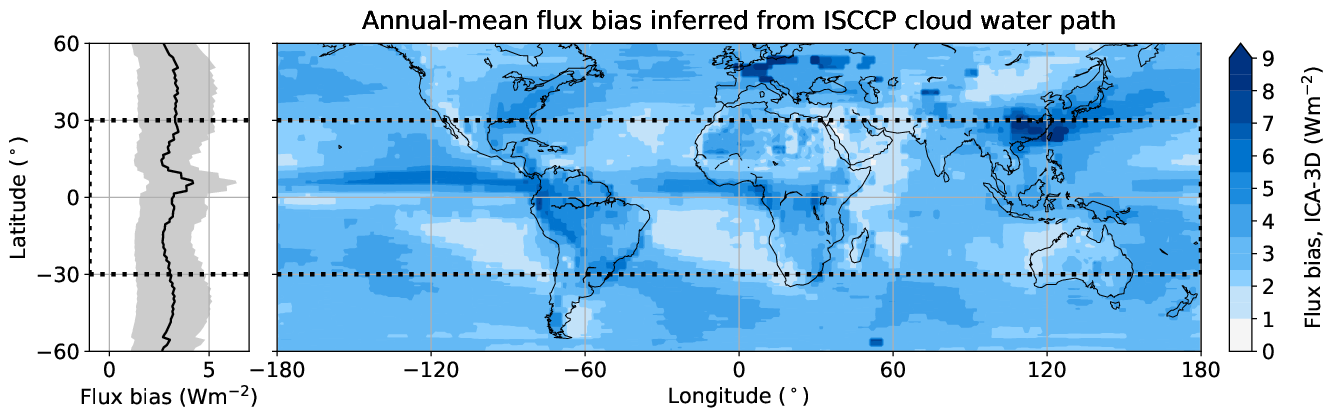

|

|---|

| Annual mean radiative flux bias in cloud-resolving models that make the independent column approximation. The results are most robust equatorward of $\pm30^\circ$ (Singer et al. 2021). |

Although this bias is smaller than those induced by unresolved cloud processes in current climate models, it is comparable to the GHG warming signal of $2.5-3.1~\mathrm{W}~\mathrm{m}^{-2}$. Moreover, it is a bias that will need to be addressed for decades to come, even in global cloud-resolving models.